Revolution in Managua

Revolution is on display in Managua, the capital city of Nicaragua. All throughout the city, there are monuments, plaques, informational displays, paintings, and other types of public homages to the heroes of this country’s most defining political movements over the past century.

Timeline (1821-1979)

- 1821: Nicaragua is part of the Central American Federation that wins independence from Spain.

- 1843: Central American Federation breaks up.

- 1909, Estrada’s Rebellion: José Zalaya, a Nicaraguan Liberal Party member, is president of Nicaragua and is collaborating with Germany and Japan to plan an interoceanic canal to rival that of Panama. At this point, the foreign policy of the United States has long prioritized making and keeping itself as the controlling influence over Latin America (Monroe Doctrine, Pan-Americanism, etc.) In order to prevent the canal project from happening, the United States backs Juan José Estrada, a Nicaraguan Conservative Party politician, to wage a rebellion and overthrow Zalaya’s government. Eventually, the United States sent marines, which helped them and Estrada succeed.

- 1909-1979: During this time the United States is significantly involved in Nicaraguan affairs, pulling the strings behind the country’s presidential elections, coups, etc. The United States obviously prefers Nicaraguan Conservative Party candidates and is wary of politicians with leftist leanings.

Our Protagonists:

- Augusto César Sandino

- Rubén Darío

- Salvador Allende

- Daniel Ortega

- Caupolicán

- Hugo Chávez

Our Destinations:

- Avenida Central

- Parque Central

- Plaza de la República / Revolución

- Puerto Salvador Allende

- Avenida Bolívar

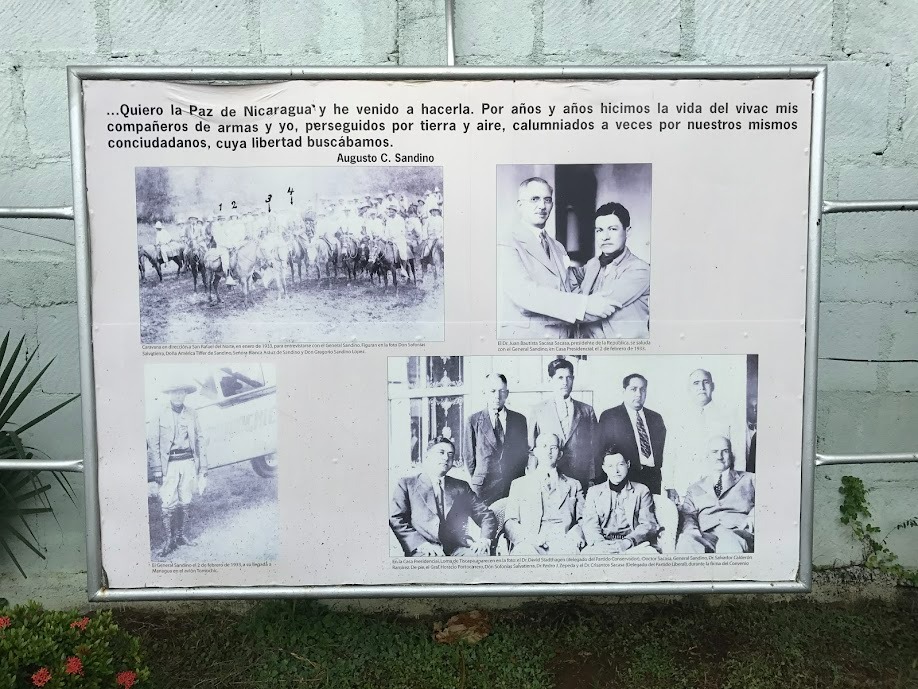

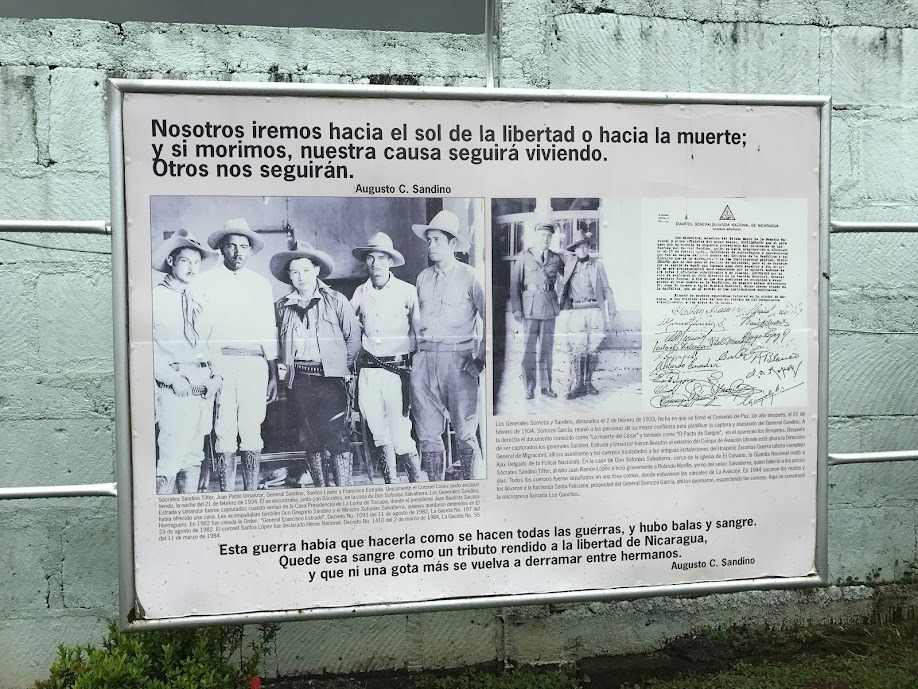

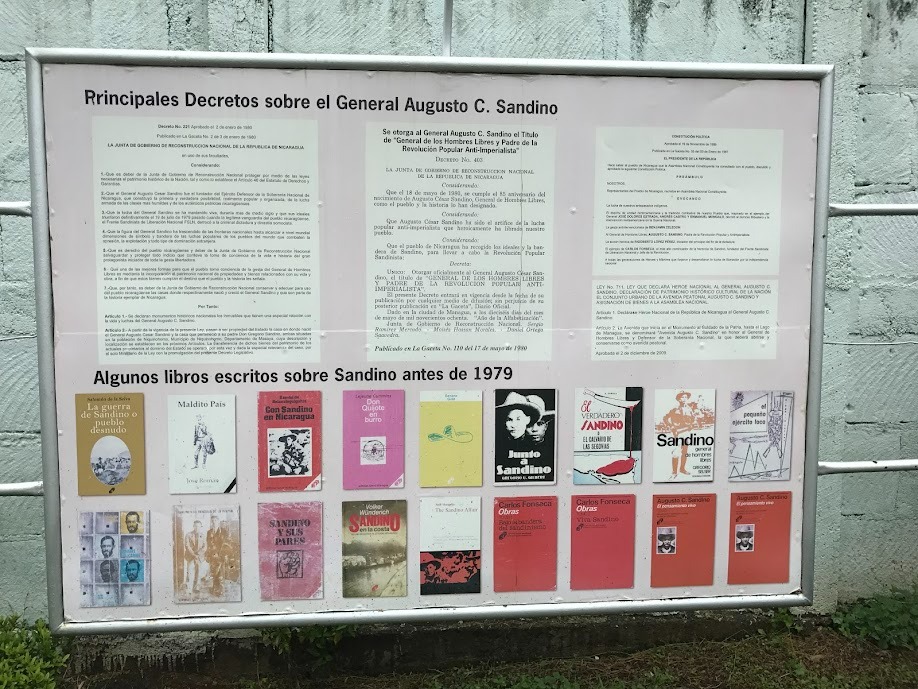

Augusto César Sandino

It’s time to meet our first protagonist: Sandino. Sandino is a legend of Nicaragua, revered (or at least publicly so) throughout modern-day Nicaragua for his role in revolution for liberation, kind of like George Washington or Thomas Paine might be by patriotic Americans in the United States.

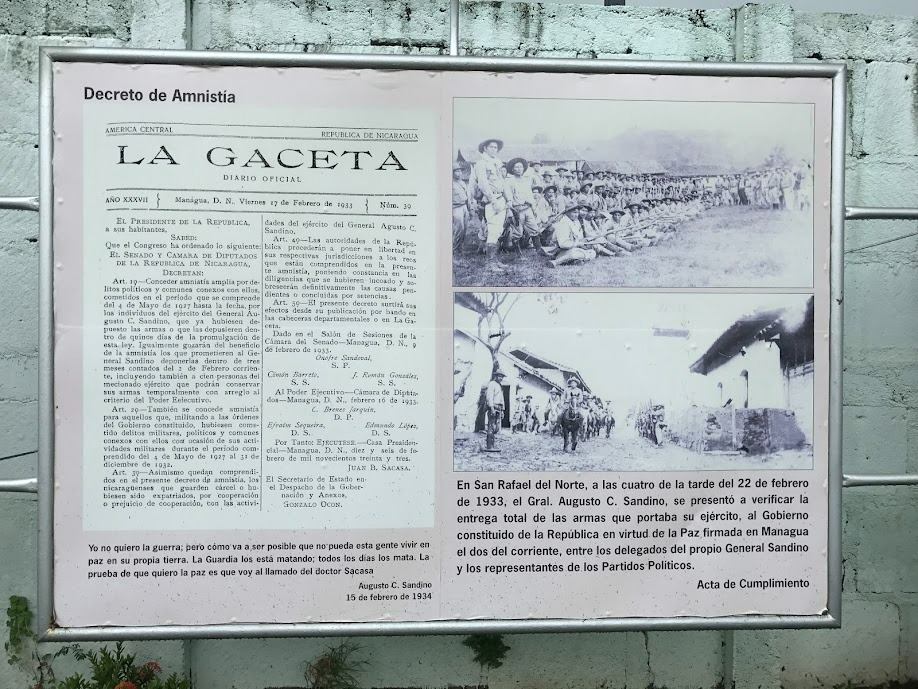

Throughout the first few decades of the 1900’s, resentment grew around Nicaragua towards United States involvement in the country’s affairs. Between 1927 and 1933, Sandino led a rebellion against the United States in Nicaragua.

In 1934, Sandino was assassinated by Nicaraguan National Guard forces of General Anastasio Somoza. In 1936, Somoza seized control of the Nicaraguan presidency via coup. The Somoza family ruled as a dictatorship over Nicaragua for the next 43 years with United States support.

Sandino is a symbol of resistance to U.S. imperialism throughout much of Latin America today. He is the man in the middle of the statue in the picture to the right. His figure is all over Managua.

On Sandino’s left and right are Francisco Estrada and Juan Pablo Umanzor, fighters alongside him in revolution.

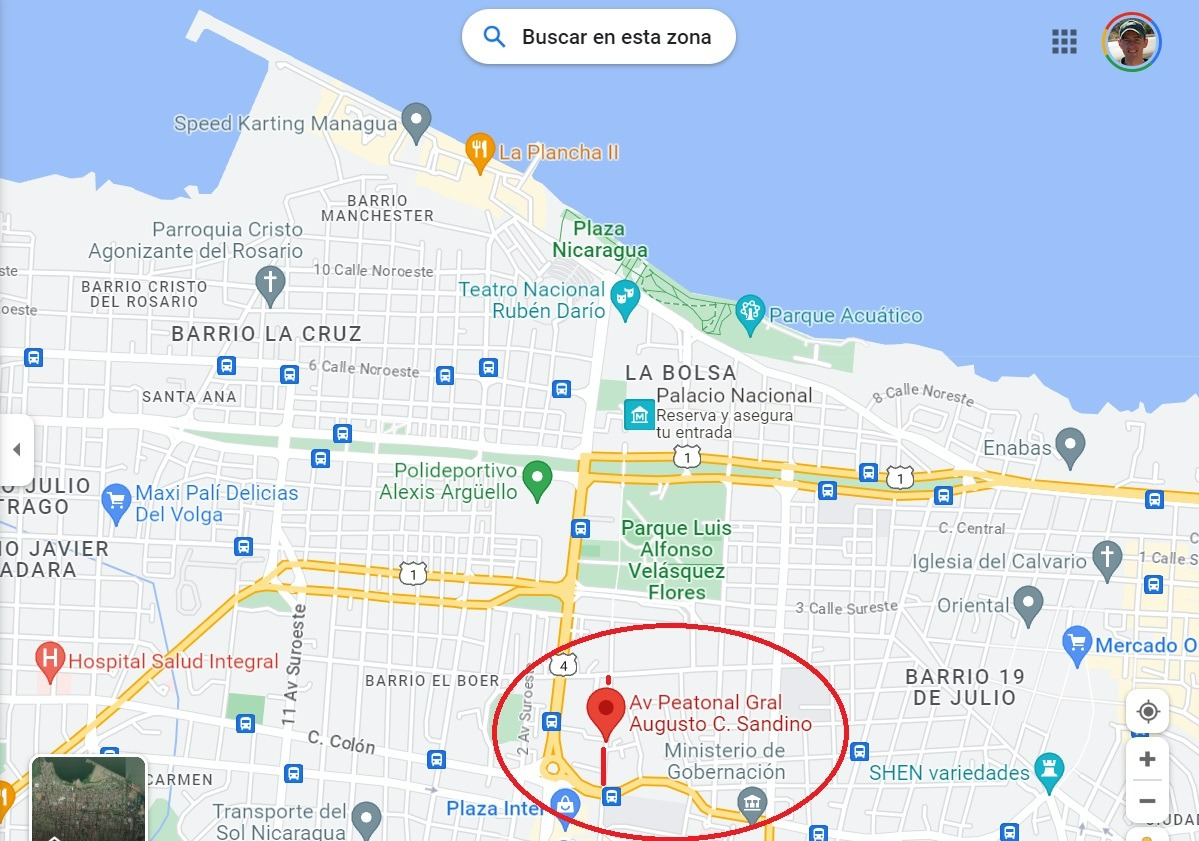

Avenida Central

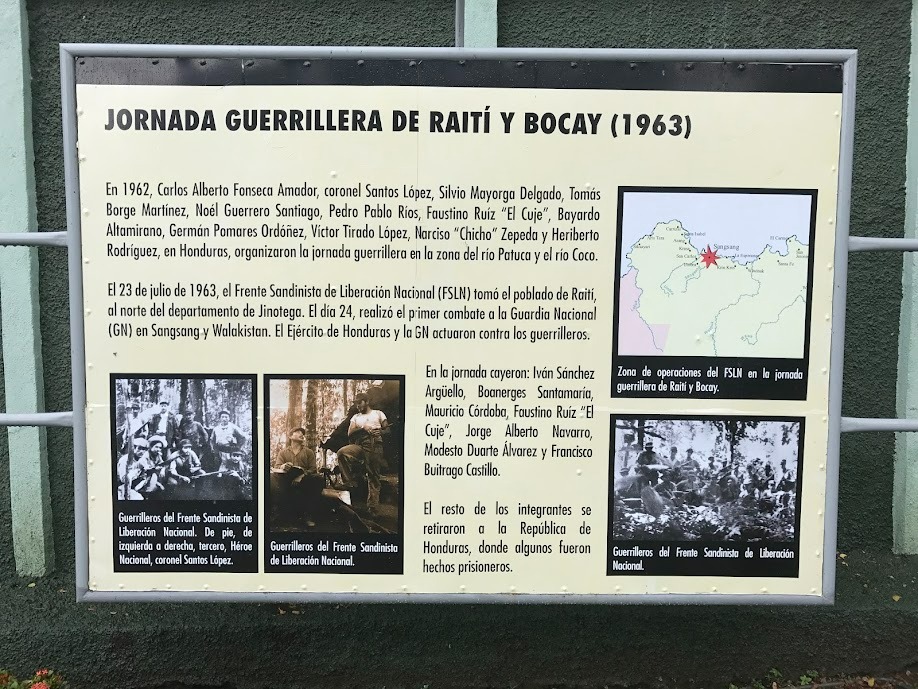

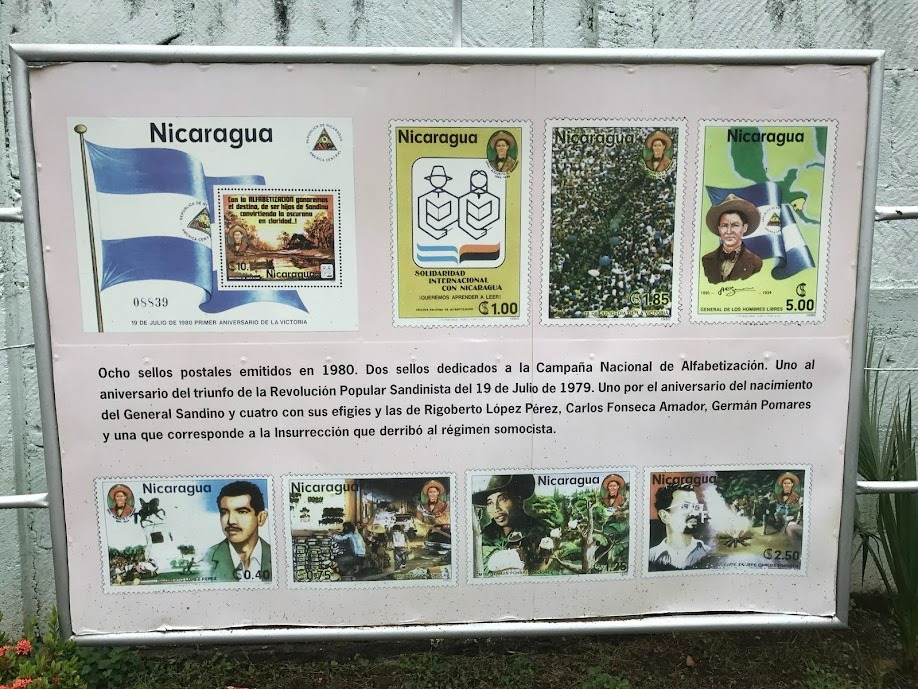

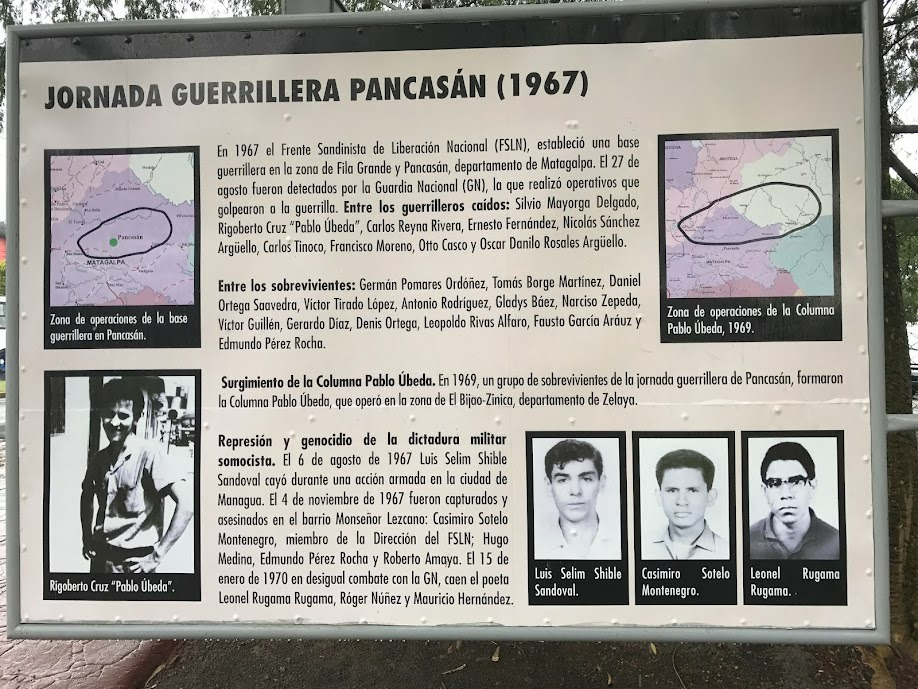

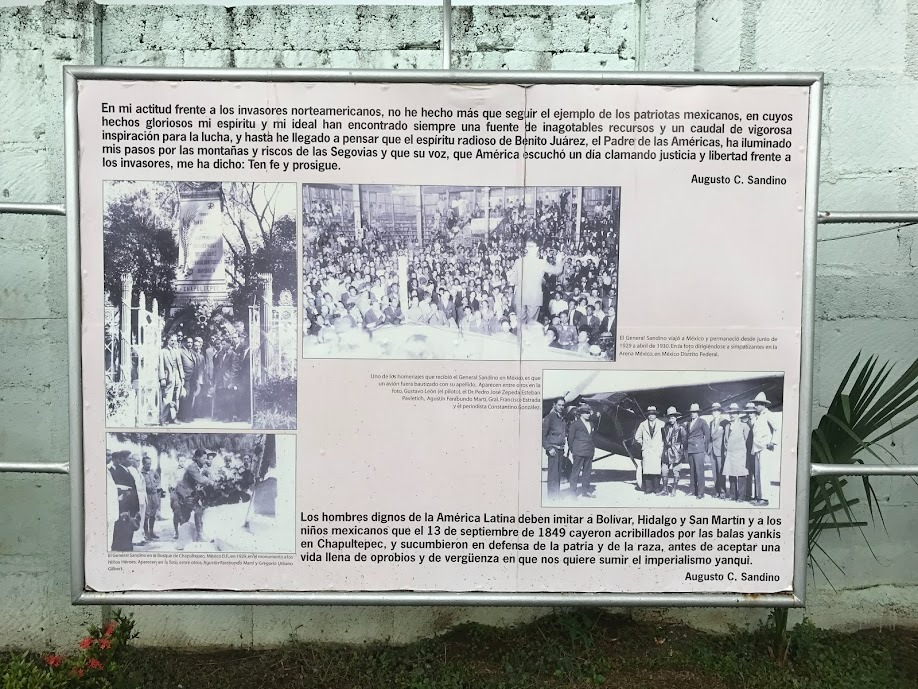

Our first stop is Avenida Central, a street in Managua that is lined with informational displays–-news articles and relics–-devoted to the Sandinista Revolution. It’s basically an outdoor history museum.

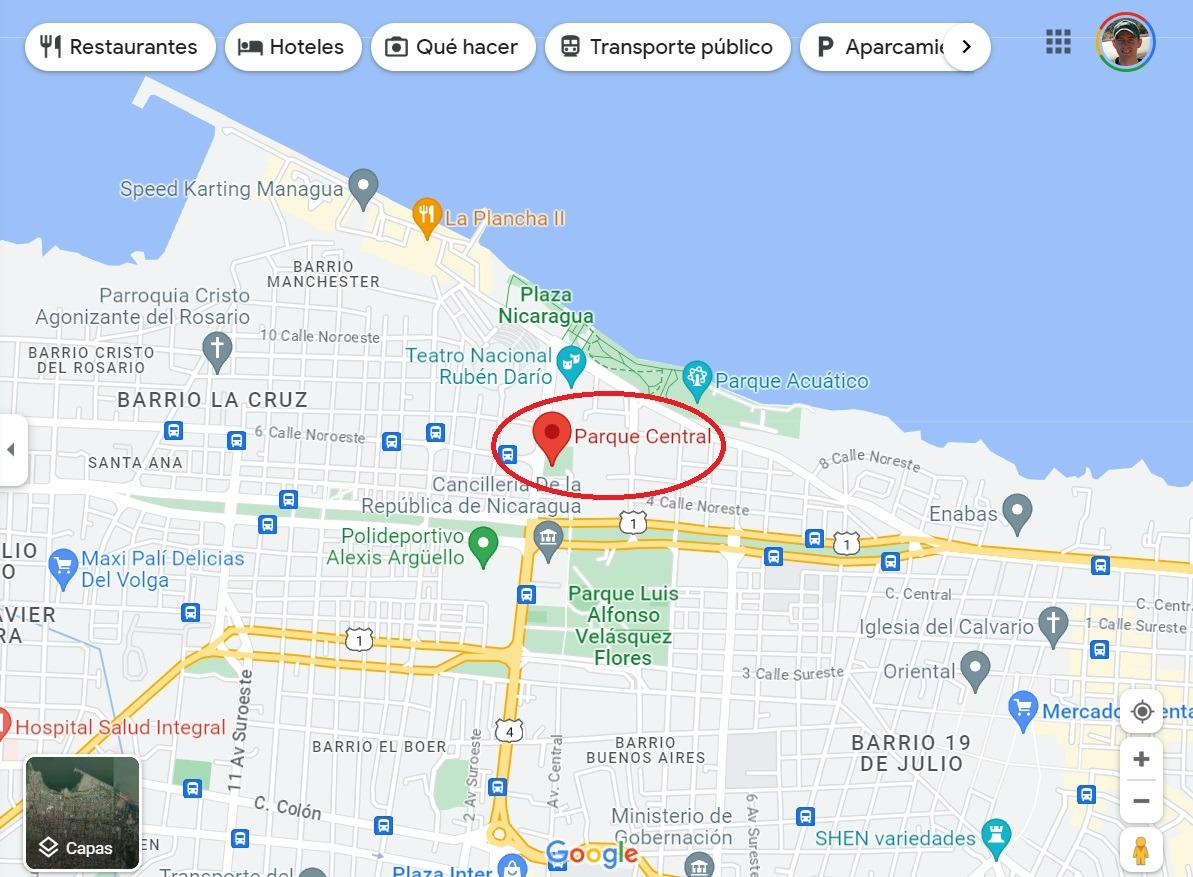

Parque Central

Our next stop is Parque Central (Central Park).

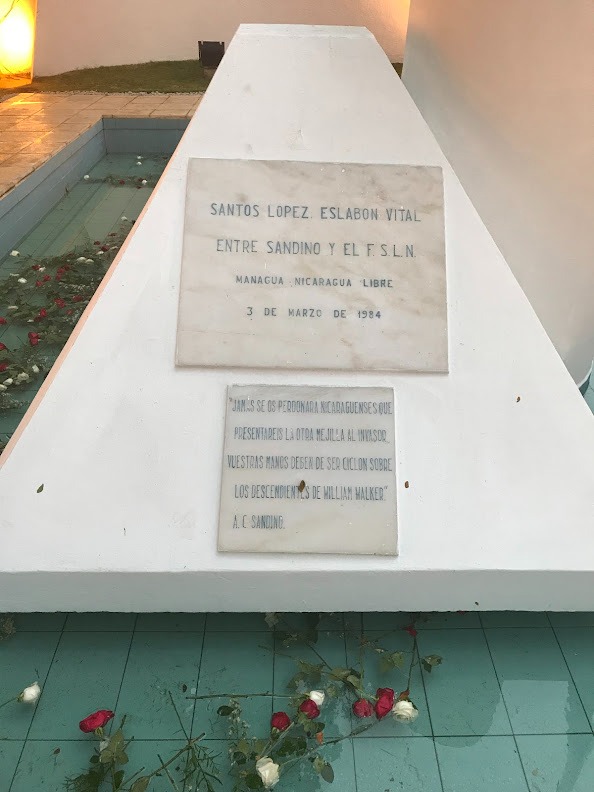

Mausuleo Fundadores

In between the park and the adjacent plaza is the Founders Mausoleum. This public homage honors the founders of the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (Sandinista National Liberation Front), the political party that overthrew the Somoza regime in 1979. Their acronym is FSLN.

Sandino wasn't a part of this party. He had been dead for 45 years by the time the FSLN took control of Nicaragua, but his fighting spirit, influence, and godlike status lives on in Nicaragua. Can you see his figure on the altar of this site, guarding and looking over it?

Sandinismo Flag

This is the flag of the revolution, or the FSLN party--The two are essentially synonymous. The FSLN is currently the ruling party of Nicaragua. These flags can be seen all over Managua. Nearly every time there is the flag of Nicaragua flying, there is an FSLN flag next to it.

As a United States citizen, this seemed odd to me. It would be like in the United States flying a Republican or Democrat party flag next to our national flag based on the party of the president that is in power. At this point, I started to wonder to what extent the revolution might be imposed by the ruling party on the people of Nicaragua?

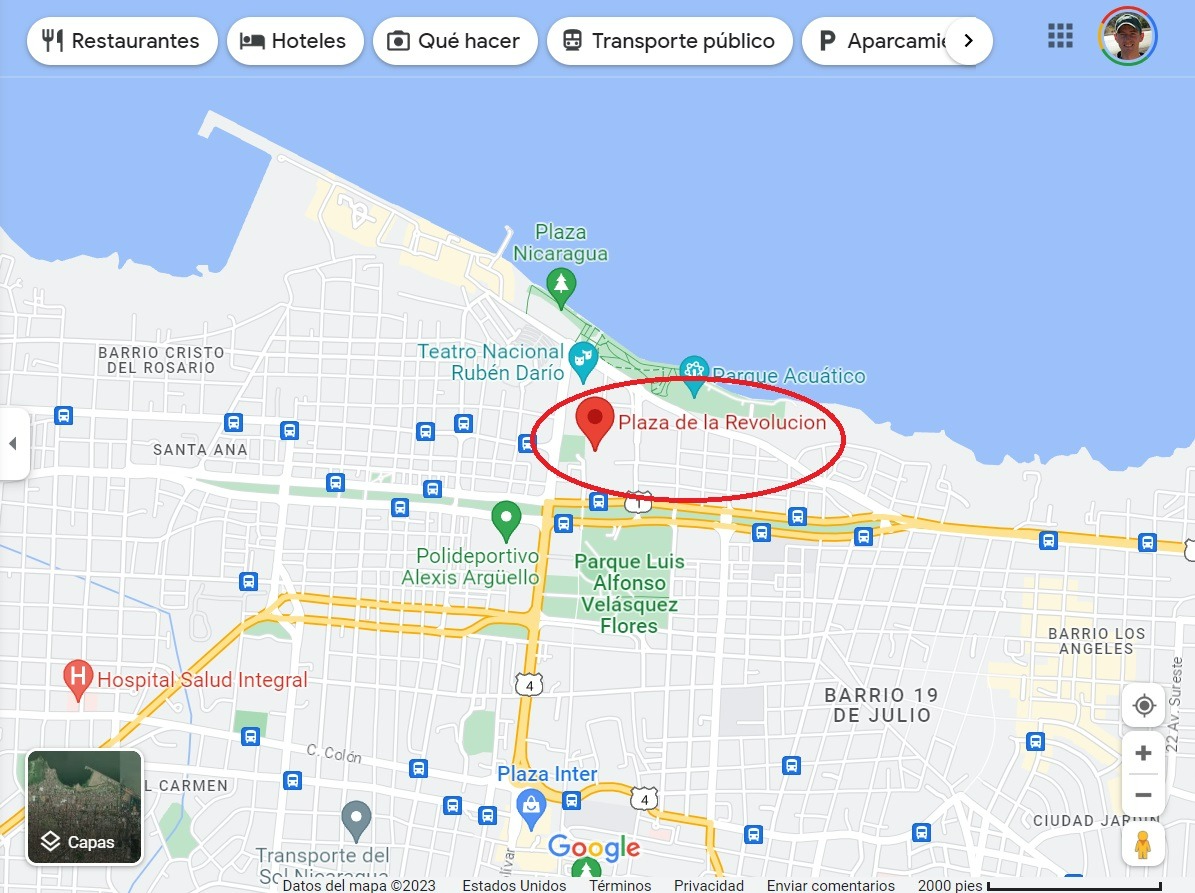

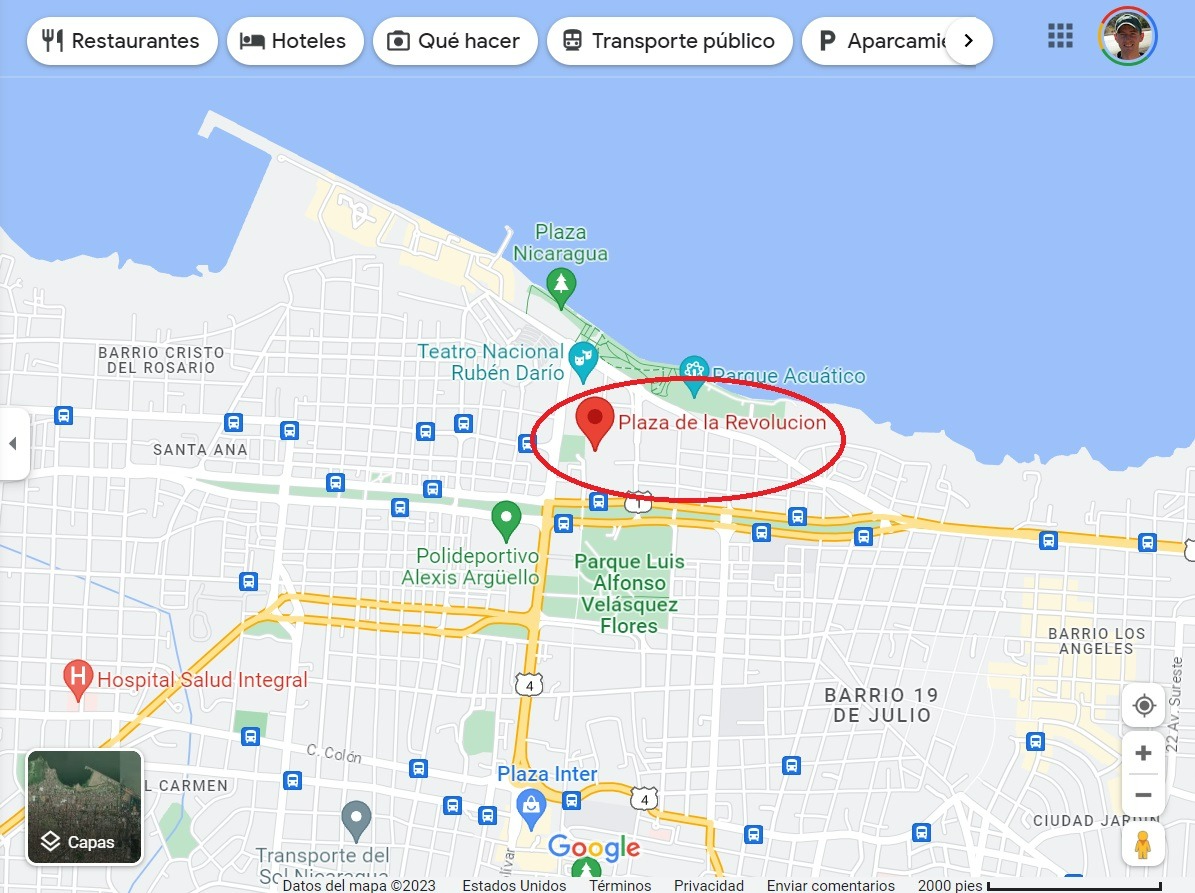

Plaza de la República / Revolución

Next to Parque Central is this plaza, which goes by both names. Again, you can see how the “republic” and “revolution” of Nicaragua are branded as synonymous.

These are the three buildings that are located around the plaza (clockwise from top right):

- Palacio Nacional: A museum of Nicaraguan history and culture

- Catedral de Santiago Apostol: A Catholic church

- Casa de los Pueblos: A government building

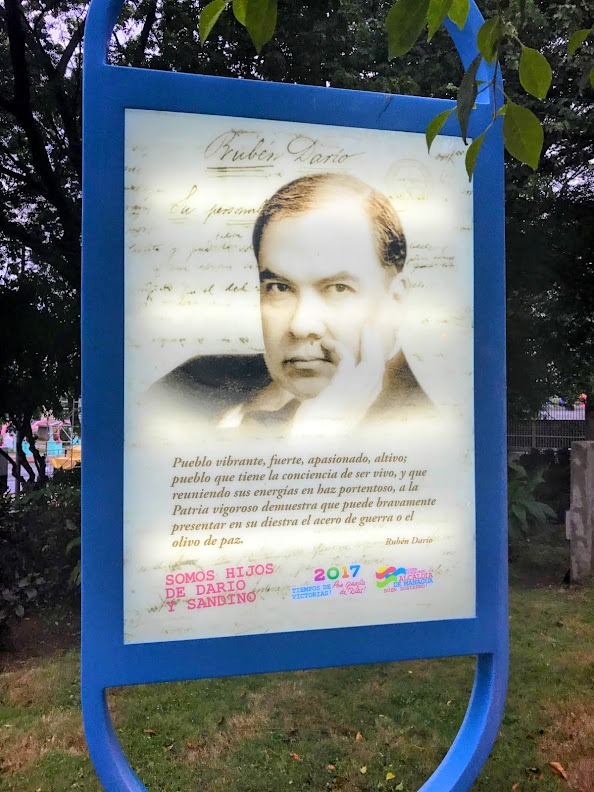

Rubén Darío

Just outside Parque Central to the north is the Rubén Darío Monument. Rúben Darío is the father of modernismo, the literature movement that permeated Latin America between 1888 and 1920. Darío stayed relatively politically neutral in his work, but here is how he is tied to the revolution:

Before the 1880’s, Nicaragua and many countries throughout Latin America were relatively new states with loosely defined cultural identities: There were historically oppressed indigenous and African populations plus elites of European descent who associated more with their European relatives than those of other ethnicities in their own country. In the early 1800’s, Latin American writers were most influenced by Romanticism and Naturalism, largely European movements.

But, as time went on and these nations matured, stronger senses of national identities began to develop among many people throughout Latin American countries. In the 1880’s, through the work of Darío, modernismo evolved as the first truly Latin American literary movement. Themes of Daríos work included defining and taking pride in the Latin American identity. As other writers followed Darío’s lead, a wave of Latin American sentiment swept through the Spanish speaking countries of the Americas, continuing to strengthen national identities across the region. Perhaps the other most recognizable modernist writer is José Martí, a Cuban man who is considered a national hero in Cuba for his role in the liberation of Cuba from Spain.

The sense of pride that modernismo helped foster among people in many Latin American countries helped create conditions for the takeover and rule by nationalistic parties that rallied on platforms of self-determination and anti-American imperialism, most notably in places like Nicaragua, Cuba, and Venezuela.

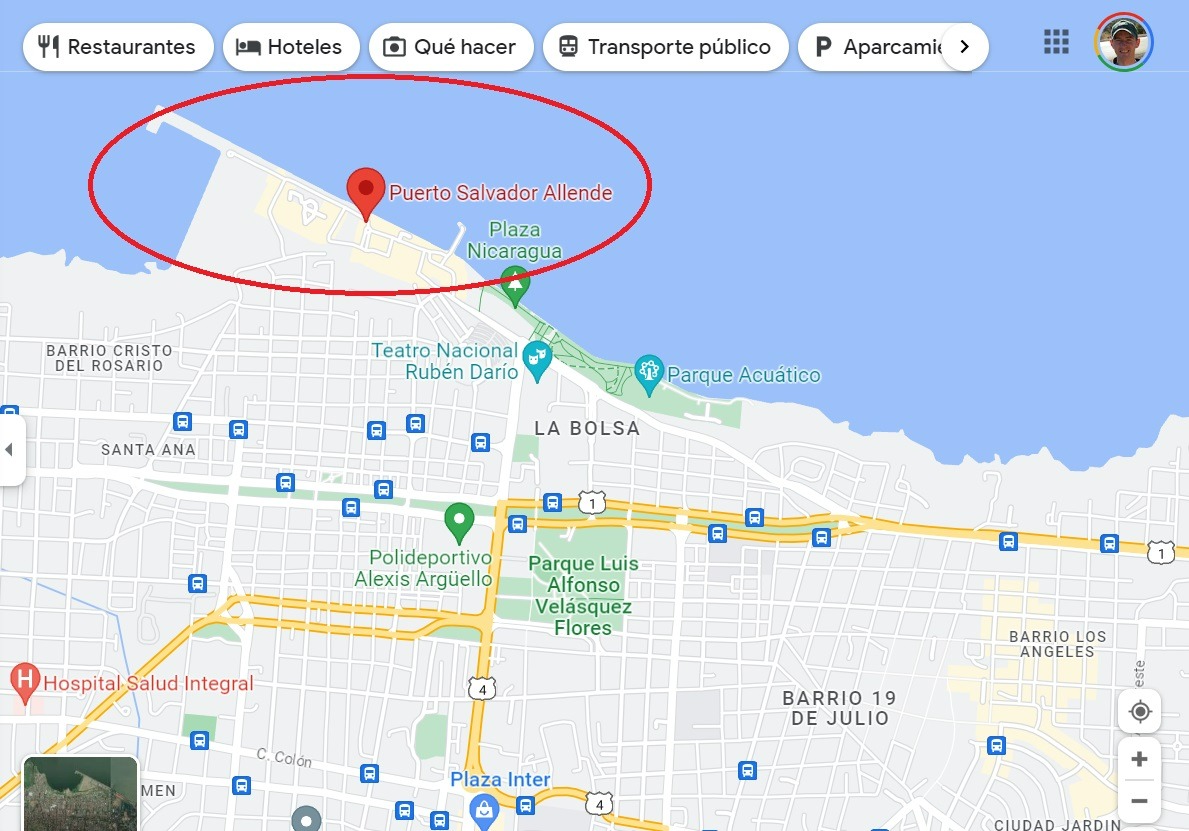

Puerto Salvador Allende

Destination #4 is Puerto Salvador Allende, a park in northern Managua that borders the Xolotlán Lake. Puerto means “port.” I was confused about this name because I didn’t see boats docking here. The area was more of a place for public recreation with restaurants, pedestrian walkways, and playscapes for kids.

Unfortunately, on the day I visited, the place was completely empty and nearly all businesses were closed. It was rainy and most people were probably waiting for the night, when the festivities for the anniversary of the Nicaraguan Revolution, which was tomorrow (July 19), would begin in downtown Managua.

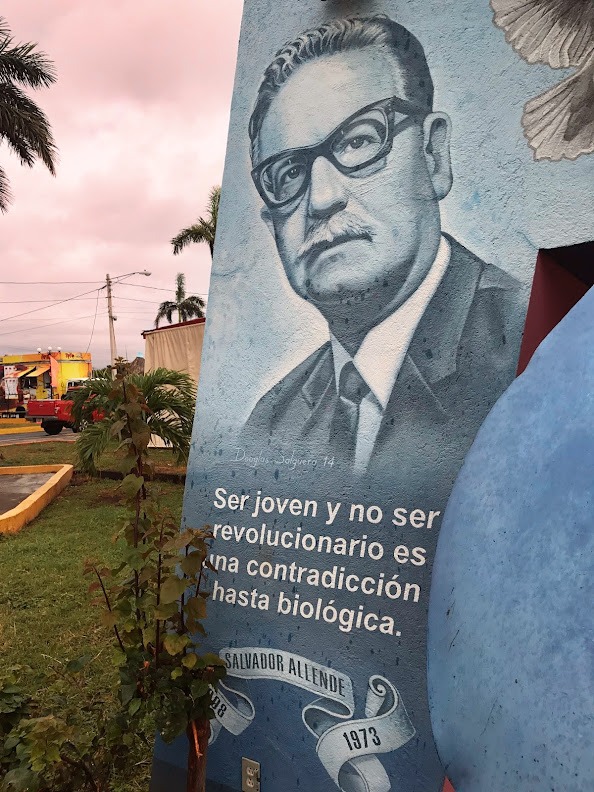

Salvador Allende

Salvador Allende was not Nicaraguan, but here is how he is tied to revolution in Nicaragua and why there is a park here in Nicaragua’s capital that honors him and bears his name:

In the 1950’s, the Cold War was under way and a key initiative of United States’ foreign policy involved stamping out communism around the world, which included its sphere of intended influence in Latin America. As a result, waves of violence roll through the region. There are U.S.-backed military groups staging coups to overthrow democratically elected leaders and establish dictatorships in a number of countries (Guatemala, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil). And, in these and other countries (El Salvador, Honduras), there are also civil wars involving U.S.-backed groups versus political groups with leftist leanings. This period is marked by chaos and sadness–-Government sponsored executions, “disappeared” citizens, etc. In Argentina, for example, during a period that is known as the country’s Dirty War, tens of thousands of people disappeared, many of which were the children of leftists and people who opposed the military regime.

However, in the midst of these trends, in 1970, Salvador Allende, a socialist politician, rises to power via democratic election in Chile. You can see now how Allende at this time becomes a hero for almost anyone in the region with leftist leanings and/or desire for their country’s self-determination without intervention from the United States, including people in Nicaragua. Six years later in 1979, Sandinistas wage rebellion versus Nicaragua’s dictator at the time, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, and take over the government with plans to institute a number of liberal reforms.

(The victories didn’t last. In 1973, a U.S.-backed military group overthrew Allende in Chile and instituted Augusto Pinochet as dictator, during which process Allende killed himself, and during the 1980’s, violence continued to rage through Nicaragua between the Sandinista government and the U.S.-backed Contras rebel group.)

Throughout Managua, every time there flies the national flag, the Sandinista flag flies alongside it, as you can see in the second picture below behind the statue of Allende.

Legends Resurface

Sandino

Rubén Darío

Caupolicán

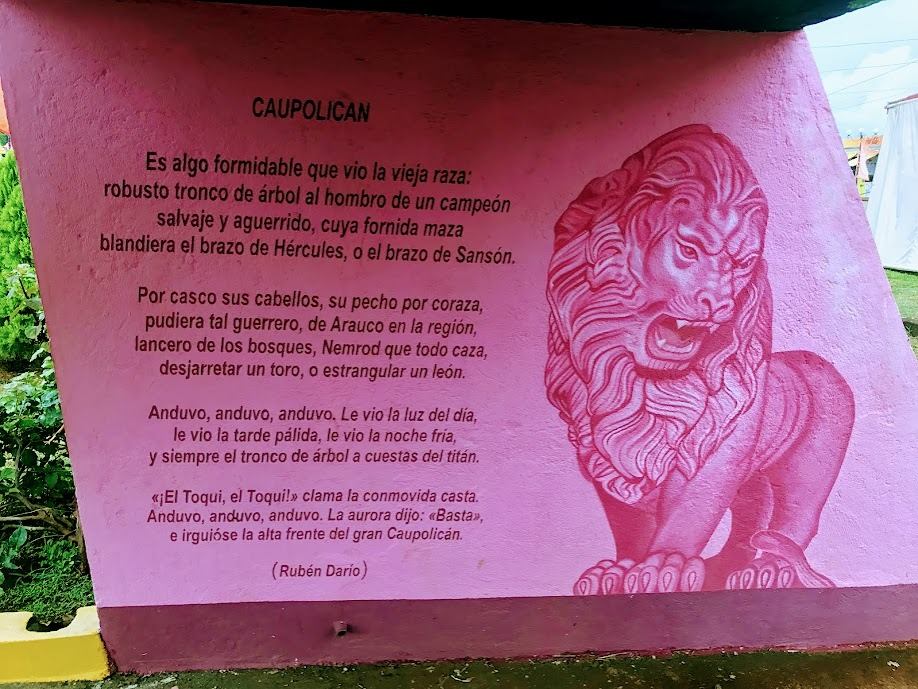

Caupolican is another character of this story of honoring revolution in Managua. A poem written for him by Rubén Darío is painted on a wall in Allende Port.

Caupolican was a warrior and leader of resistance to the Spanish by the Mapuche people, an indigenous group who has lived in parts of modern day Chile and Argentina, some archaeologists say, since 600 BC. He was Mapuche Toqui, or chief, around 1553-1558. He is another symbol of resistance to foreign intervention for this region of the world.

The poem views Caupolicán in a positive light and praises his strength.

Branding the Revolution

At this point, I’m beginning to realize how much a part of the revolution branding is.

I sometimes hear in conversation and in the news about countries that are “in revolution:” Nicaragua, Cuba, Venezuela, for example. I hear leaders in these places say things like, “Qué viva la revolución,” which makes me curious because throughout my life I associate “revolution” with actual conflict, so how can there be revolution in these countries, but I’m not hearing or reading about any ongoing civil war? For the first time, I realize that “revolution” is a state, or condition. When “revolution” takes control of a place, even into this place’s post-conflict era, leaders often declare it as continuing to exist so that they can continue to sustain the nationalism and pride that they have managed to build around it throughout their country.

Check out how the benches throughout Salvador Allende Port are painted with motivational and patriotic slogans, as well as the declared values of Nicaragua’s ruling FSLN party.

He's Everywhere... (and so is the flag...)

Daniel Ortega

But, nationalistic pride forged around “revolution” can lead to lasting and oppressive regimes (at least that’s how I understand the current regimes of Nicaragua, Cuba, and Venezuela to be).

At this point, let’s meet another protagonist of this story, Daniel Ortega, the leader of the FSLN since 1979 and twice president of Nicaragua, first from 1979-1990 and again from 2007-present. Since participating in the Nicaraguan Revolution of 1979, he has amassed a ton of power and influence over Nicaragua. In addition to being leader of the largest political party in the country, his family owns and/or influences the majority of television channels in the country.

Ortega and his government have been increasingly cited by Amnesty International for repression of political opposition and human right violations.

Since 2014, protests have been common in Nicaragua as a way for people to voice their dissatisfaction with the government, which they claim is corrupt, increasing taxes, decreasing benefits, etc. In 2018, Daniel Ortega ramped up his response to these protests by declaring political demonstrations illegal and increasing the use of violent responses by his forces to suppress dissidents throughout the country.

When I was traveling by myself through Nicaragua in 2017, I spent a few days hanging out and talking with the guy who was working the front desk of the hostel where I was staying in Granada, a colonial city just south of Managua. It wasn’t very busy and there was a lot of down time to chat. His name was Juan. In 2019, Juan sent me some messages showing himself in a sling, explaining that he had been in prison and had his arm broken at the hands of police, and asking if I knew any way to find work in the U.S. or Canada. I can’t confirm his story obviously, but it was both sad and interesting to be touched by this real-world story of the situation unfolding in Nicaragua at this time.

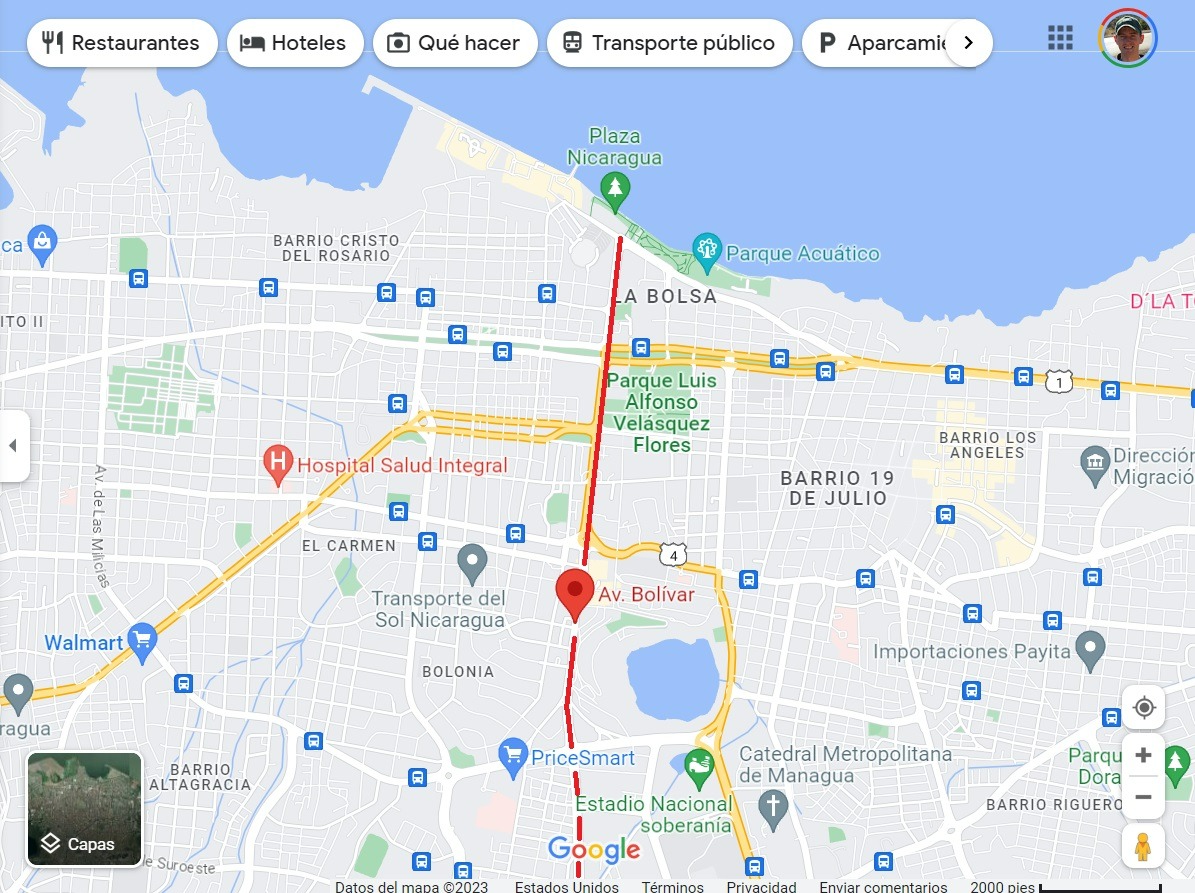

Avenida Bolívar

The final destination of this tour is Avenida Bolívar, a main road of Managua that is also named in the spirit of revolution, this time for Simón Bolívar, the revolutionary and Latin American hero who helped liberate the modern day countries of Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia from the Spanish Empire.

You can see that as the day goes on and night falls, the street gets livelier and livelier. That's because tonight (July 18) starts the festivities to celebrate tomorrow's anniversary of the revolution.

38th Anniversary of the Nicaraguan Revolution

I happened to be flying out of Nicaragua on July 19, the day of the country’s Anniversary of the Revolution. This year, 2017, was the 38th anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution led by FSLN Party, including Daniel Ortega. As I walked around Managua the night before, venues were already set and the festivities already beginning.

You can see in the decorations more of the government’s branding on display everywhere: Banners showing a smiling Daniel Ortega side-by-side with a portrait of Sandino, advertisements for the Ministerio de Economía Familiar, the government agency in charge of curating an economy for the benefit of Nicaraguan families, and the same slogans that we saw on the benches in Allende Port.

In the last picture, you can see a car driving around flying the Sandinista flag from its window.

Hugo Chávez

To this day, there are close alliances among the Latin American countries where “revolution” is still ongoing and the government rallies support around anti-U.S. imperialism, namely Nicaragua, Cuba, and Venezuela. These are the same countries that are allied with U.S. adversaries around the world: Russia, Iran, China, etc. In 1999, Hugo Chavez rose to power in Venezuela and ruled the country as a socialist president until his death in 2013. Chavez is a “brother of Nicaragua in socialist revolution.” He is honored here in Managua at the Rotunda Hugo Chavez.