Panama Canal

Intro

Getting to visit the Panama Canal was one of the highlights of my life up until this point. It was so cool. We grow up in the United States learning and hearing about what a massive feat of engineering the Canal is and how it has changed the world. Before it, in order to get from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean, ships had to travel all the way around South America, which was an extra 18,000 nautical miles of journey. Finally seeing the Panama Canal in person with my own eyes felt like a dream come true.

History, Part A: The Spanish Idea

The Panama Canal was initially the idea of Spanish Emperor Charles V (known in Spanish as Carlos I de España y V del Sacro Imperio Ramano Germánico, or Holy Roman Empire). He realized how valuable the isthmus of Panama could be as a potential connector of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In 1534, Carlos V signed a decree ordering the regional governor of Panama to study how to make it happen.

History, Part B: The French Attempt

That said, construction of the Panama Canal wasn't actually pursued until 1881 when French engineers who had just successfully built the Suez Canal in Egypt to connect the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, high on confidence, thought that they would give the Panama Canal a try. They ran into three issues in Panama, however, that they hadn't encountered in Egypt:

1) The terrain in Panama was mountainous compared to the relatively flat surface of Egypt, which made digging through the land significantly more difficult and costly.

2) While the sea levels of the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea were relatively even, the French engineers hadn't realized that the Pacific Ocean was 20 centimeters higher than the Atlantic Ocean, which would have created challenging currents through the canal.

3) Yellow fever--The disease decimated the population of French canal construction workers.

Ultimately, France had to abandon the canal project.

History, Part C: U.S. Construction

In 1904, the United States took over the project. They succeeded because instead of trying to dig completely through the mountainous terrain all the way down to sea level, they came up with a way to kind of route ships up and through the land. They still had to dig and it was still immensely difficult--The United States recorded 5,855 canal worker deaths during its time in charge of construction from 1904 to 1913--but not as much as the French had attempted. (During the French effort, over 22,000 workers died.)

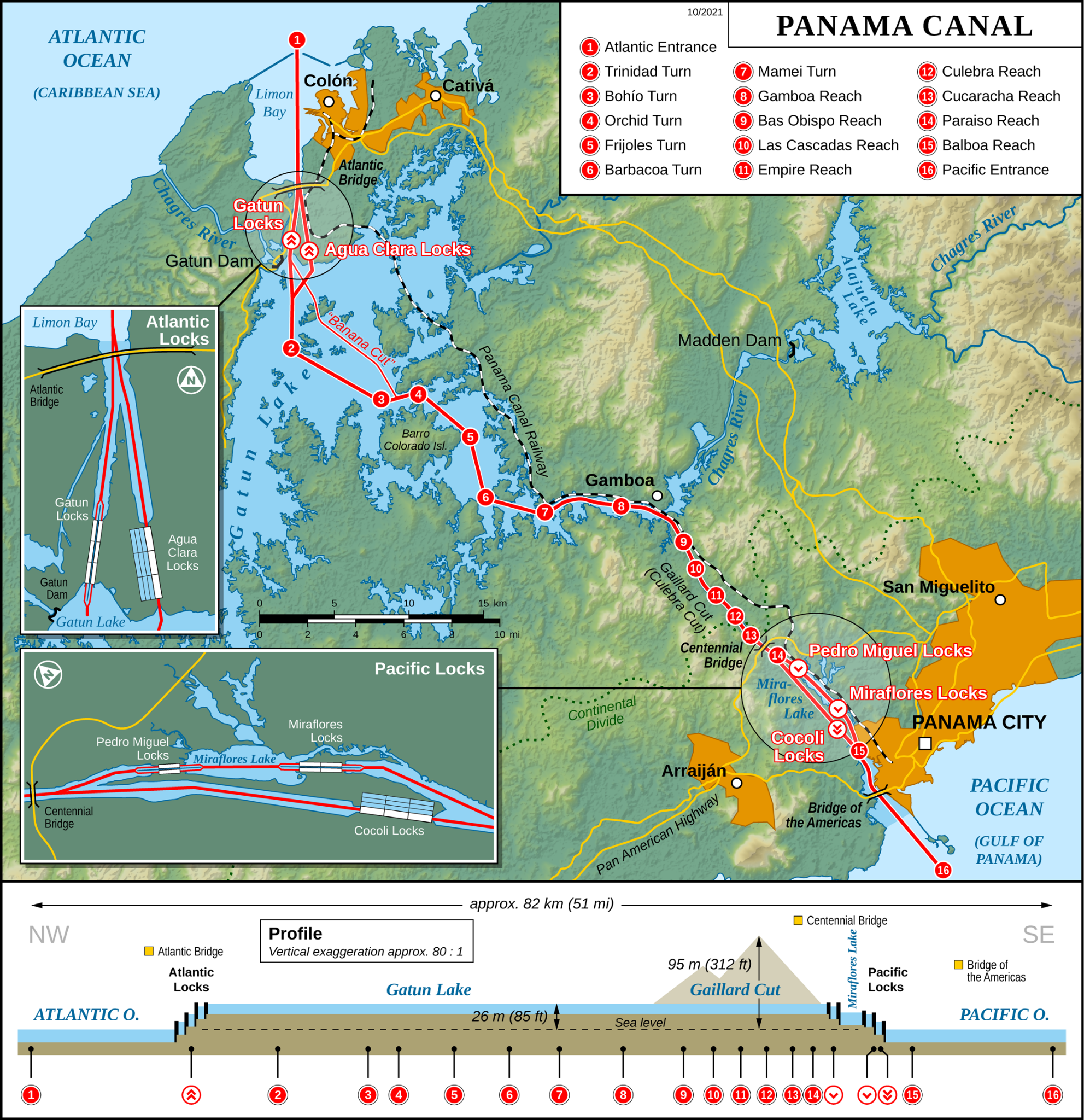

In order to implement their plan, United States engineers first built Gatun Lake in the middle of the isthmus at an elevation of 85-feet (26 meters). Then, they built a series of locks on either side of the lake that would raise ships from one ocean to a waterway that includes lake through which they would travel, before lowering them to the ocean of their destination on the other side.

You can see a map of the canal below. After that is a video that really well explains the history of the canal--The French effort, the U.S. plan, and how the canal works.

History, Part D: Nationalization

There is a really cool story by the Radio Ambulante podcast about life in Panama in and around the Canal Zone during United States control of the canal throughout the first half of the 20th century. Here is a link to the episode: https://radioambulante.org/transcripcion/la-zona-transcripcion

In 1977, United States president Jimmy Carter and Panamanian president Omar Torrijos signed the Torrijos-Carter Treaties, which began the process of handing control of the canal over to the Panamanians. This process was completed by December 31, 1999, at which point the Panama Canal Authority assumed full control of the canal.

History, Part E: Expansion

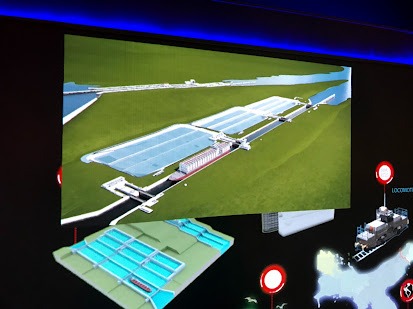

In 2007, Panama started the Panama Canal Expansion Project, which would add a new lane / set of locks on each side of the canal. Not only would this accommodate more ships and increase the capacity of the canal, but these new locks would be built with water saving basins that would make more efficient the canal's use of water.

I'm not an engineer, so I'm not going to attempt to explain these new constructions in detail. You can certainly read about them, though, on your own. Here is a link to the Wikipedia page about the expansion project: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panama_Canal_expansion_project

You can see the Agua Clara and Cocoli Locks labeled on the map above. Below is a picture that I took from the Miraflores Locks Visitor Center that shows the design of the new locks with water saving basins.

Current Operations

The Panama Canal is open 24/7. The canal is approximately 50 miles long. Around 40 ships pass through the canal each day. Ships pay by weight. It normally costs a ship tens of thousands of dollars to pass through the canal. It takes on average 8-10 hours to traverse the Panama Canal.

Many websites write about how "each set of locks has two lanes, which accommodates ships traveling both east-to-west and west-to-east at the same time," but this was not the story that I heard when I was in Panama visiting the canal. In Panama, I learned that simultaneous multi-direction travel through the canal does not happen and that instead, ships travel one way through the canal for designated, abbreviated periods of time.

Pictures & Videos from Miraflores Locks

I visited the Miraflores Locks. These locks are close to Panama City, where I was (and most tourists will be) staying. They also cater more to tourists than the Cocoli locks, the "new locks" on the Pacific side, as they have existed for longer and have a visitors center with museum for curious tourists like me.

The Facility from Outside

Ship #1

Here, you can see a barge enter the first lock of the Miraflores lock system.

Then, the ship sits in the lock while the water shifts from one lock to the next in order to either raise or lower the ship from one water level to another. In this case, you can see that the ship is being lowered, which means that it is near exiting the canal. The Miraflores Locks, where I am while taking these pictures, is on the Pacific side of the canal, so we can deduce that this ship is traveling from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean.

Two Ships at Once!

This moment was so cool, when a second ship entered the first Miraflores lock--One ship high, one ship low, in the first lock, only one more to go.

Shifting Water

This video shows water draining from the first lock into the second. When the water levels in each lock are even, the gates will open and allow the ship to pass through.

The gates open! The first ship begins to pass through!

You Shall Pass!

The Exit

Even the landscaping adjacent to the locks is amazing:

¡Adiós, barcos! Buen viaje.

But they don't stop coming...

Post a comment